Community Commons – Island Entertainment and Social Get-togethers Post World War II

Part 13 – Ahhhh…those Wonderful Flying Boat Days!

People often congregate for important economic reasons but then chat, swap yarns, socialize and gossip, whilst participating in the ‘main event’. Some of the earliest communal events in Island life were the ship days, where Islanders would gather at or near the landings (Wilson’s Landing or Ned’s Beach) to collect freight, mail, meet or farewell friends, family or guests – but let’s not forget, to also meet up with each other!

Once flying boats started to operate (1947-74), their arrival and departure also created a vital economic and social hub. The flying boats landed and moored in the Lagoon near the jetty so, naturally, the first facilities to be utilised were inherited from earlier shipping operations: a solitary cargo shed at the top of the jetty with a tiny lean-to office described as “akin to a bush toilet”.

To get a feeling for the social “buzz” created by the flying boat arrivals, we could do no better than quote Frank Chartres, who made 36 trips on the flying boat between 1966 and 1974 and was, perhaps, the most travelled passenger from that era: “Then, of course, the mere departure and arrival of the flying boat was an ‘Island event’. You had, what, 42 people leaving at the same time and you’d all make friends on the Island so everybody – all of the tourists and most of the locals – went down to the jetty to see them off, and to see what sort of ‘talent’ was coming in on the flying boat as you’d get the same number of people arriving. Of course, those leaving were nearly always presented with leis made from hibiscus… Everybody would have liked to take them back to Sydney but the tradition was that you threw them into the water from the launch as you went from the jetty to the plane and they, of course, floated. I think, this meant you’d return to the Island …if it was washed onto the beach and, by and large, they always did because there wasn’t anywhere else they could be washed!”

It would be difficult to under-estimate the social importance of the hub created by flying boat operations on Lord Howe. Prior to 1958, all airline operations at Lord Howe – Qantas, Trans Oceanic Airways and Ansett – had been managed by Island residents acting as company agents.

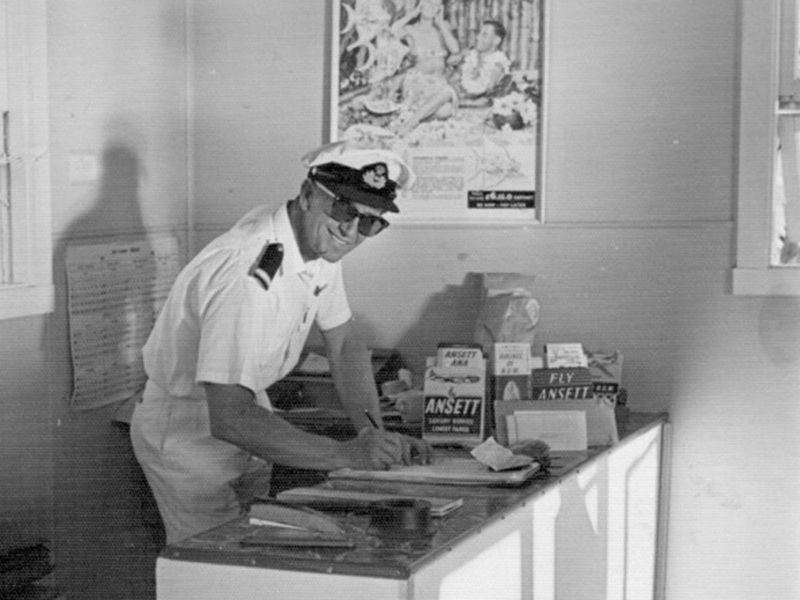

However, in March 1958, Ansett took the significant step of posting a full-time employee to manage its Lord Howe operation – David Murray – who held the position for 16 years from March, 1958, until September, 1974. David overhauled the Lord Howe end of the operation, not only improving the logistics of aircraft turnarounds but enhancing their social ambience with the construction of a new passenger terminal, ‘Welcome to Lord Howe’ signage – and even piped music which generated a distinctive Island ‘vibe’.

David’s pre-Lord Howe days contain a bundle of interesting experiences: as a child, he won a scholarship to St Andrews Cathedral school because of his ability to sing in the choir; he regularly saved his pocket money, taking joy flights over Sydney with dare-devil pilot, Henry Goya Henry (once described as the ‘pirate of the Australian skies’ who lost his pilot’s license for flying unauthorised under the Sydney harbour bridge!); in 1941, at seventeen, David volunteered for the Australian Army but, as his father was already serving in the Middle East, he was drafted into Citizen Military Force (home defense); whilst in the CMF, he trained as an anti-aircraft gunner, a bombardier on 155mm artillery, and was manning a searchlight at Watson’s Bay when the Japanese midget submarines attacked Sydney in May, 1942; post World War II, David acted in lead and supporting roles in propagandist “New Theatre” stage productions; he hitch-hiked around England and Europe for about 12 months in 1949-50, when international travel had only just restarted after the war. Life on Lord Howe Island must have seemed quite extraordinary, as David later described all these events and occupations as “rather dreary”!

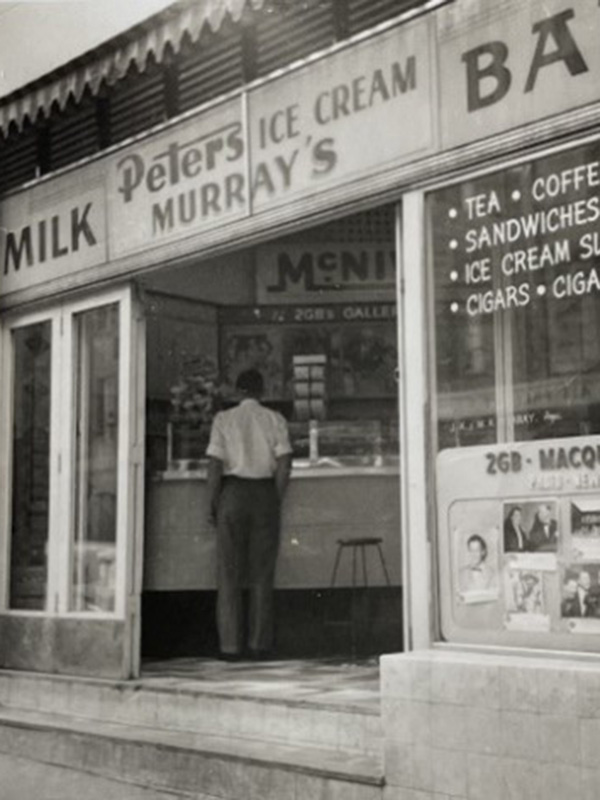

David joined Ansett in December, 1956, after he had received an invitation to apply for a job there. At the time, he was temporarily minding his father’s milk bar in Philip Street, Sydney, following an accident which tragically took his mother’s life. Two years later, he successfully applied for the job as Ansett Flying Boat Manager at Lord Howe.

However, when David arrived at Lord Howe, he discovered the flying boat operation was plagued by cramped facilities where up to 42 passengers, baggage and freight all jostled for room inside one (not-very-large) cargo shed. His office was a small cubicle on one side of this cargo shed which had standing room for himself and one passenger only. The entire flying boat area needed a revamp to facilitate flying boat turnarounds – not to mention the many social interactions that flowed with visitors and locals who congregated for these special events. David particularly saw the importance of extending a friendly welcome to every visitor who stepped ashore at Lord Howe. The paper, Biz Fairfield, reported “Coming ashore by launch, a personable young man In Ansett-A.N.A. tropical uniform (white shorts, shirt, etc.) is at the steps to greet the visitors – a cheerful, efficient young man called David Murray. As Ansett-A.N.A. representative on the Island, he has a cheerful ‘Welcome to Lord Howe Island’ for each passenger as he helps them ashore, and he spares no effort to serve them during their holiday”. (1/7/59, P.24)

These are his recollections:

David Murray

“My mother [Millie Murray] was visiting my sister [Ann Mills], who lived in Wagga at the time, and she had what seemed to be a trivial accident – a falling over and a dislocation of her hip bone which turned out to be fatal in its post operative effects. Anyway, my father had to stay in Wagga to sort things out down there. He had a small sandwich shop in Phillip Street in Sydney, so he asked me to look after that for a week until he could get all the details sorted out – which I did. Phillip Street was adjacent to the Ansett city terminal.

It was there I met a guy called Lex Strong, who was the stepson of Colonel Tom Eastick who was, in turn, NSW Manager of Ansett Airlines. And it was Lex Strong who mentioned that they were short of a traffic officer at Rose Bay, and would I be interested – which I was.

So I began working with Ansett Airlines in December, 1956. At first, I worked at Mascot on the land-based planes. At that stage, I think there were five DC3s, two Super Convairs owned by Ansett, one Super Convair on charter from Hawaiian Airlines and two Sandringham flying boats which looked after the flying boat services. They, in turn, operated from Sydney to Hobart, from Sydney to Brisbane (Redlands Bay) and also flew on to Hayman Island, which was being developed as a holiday area.

Well, about 15 months later, and it was only by chance by the way,… I heard the job at Lord Howe Island was open for grabs. I was interviewed by Stewart Middlemiss, who was manager of Ansett Flying Boat Services, and he gave me the job of Manager at Lord Howe Island. I’d been there about a month or two before …on a familiarisation flight which was quite permissible – just to let the Traffic Officers get to know the operation and see what things were like at the point of destination. I went over for the turnaround of the flying boat and came straight back. I only had half an hour to look around the place but I was very impressed with what I saw as far as its natural beauty was concerned.

[When I first arrived at Lord Howe] Everything had to be done either on foot or wheels because there were no telephones. The point of arrival was the jetty at Lord Howe and the jetty had a freight shed at the top and adjacent to the freight shed there was another small building [for an office] – I suppose you’d say it was reminiscent of a bush toilet! There was the freight shed and, on a wet inclement day, you can imagine the confusion: luggage and freight being off-loaded from the plane; luggage and freight to be moved down the jetty and onto the plane; and all the passengers who’d arrived and all the passengers who were leaving, all crammed in this one not-very-large shed which was used for the storage of freight…

Well, something had to be done, so I approached the Board, and I approached the Airline, and I made a deal with them both that the Company buy the materials and the Board erect the building.

It was a fairly simple building about 40 by 15 ft [12 X 4.5 metres] but it was quite adequate for the occasional wet or rainy departure and arrival, and it was certainly an improvement on the other process via the freight shed.

Apart from the natural beauty, there was nothing to say it was Lord Howe Island. On a railway train, you look out the window and say, ‘I’m at Woolloomooloo or Wagga Wagga’ or whatever, so I started to get the jetty painted and had a notice on the freight shed saying ‘Welcome to Lord Howe Island’. I also immediately got over a record player and some records for brightening up the arrival of the passengers, mainly island type records that you’d hear at Honolulu or wherever else. They were synonymous with islands and, therefore, it seemed quite appropriate to play them at Lord Howe…

When I first arrived, the flying boats were coming twice per week – on Tuesdays and Saturdays from Sydney to Lord Howe. In wintertime it would be one service per week, sometimes one service per fortnight, and that was a nice time for me to relax. Finally, of course, as the place became more popular and, as many people began to talk about the improvements in the accommodation as well as the airline service, we were having up to four and five flights per week.

This doesn’t sound much but can be quite hair-raising when the Island was full of people, as it was over the Christmas period, and with practically every bed having a body in it, and then having a plane overnighting because of weather conditions or engine problems, and where to put all these extra 42 people?!

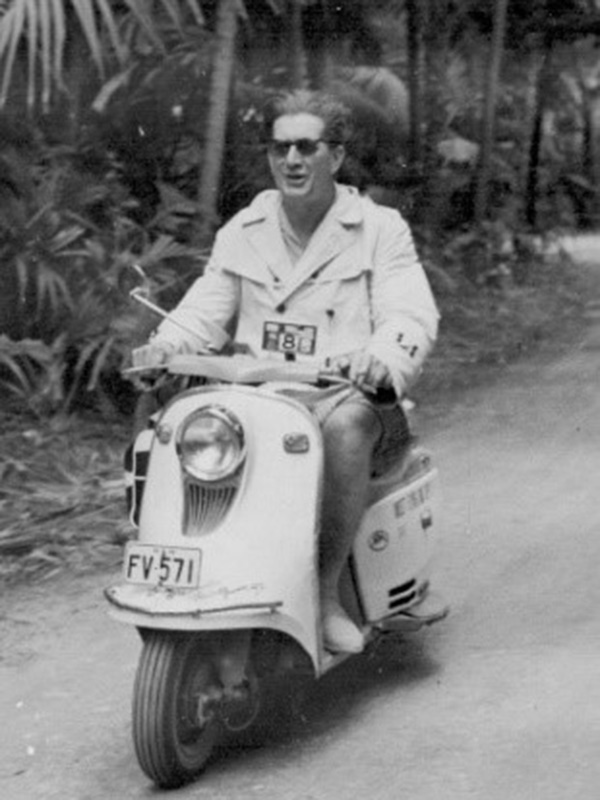

I started off with a pushbike but ended up with a motor scooter. The Company supplied me with a motor scooter which was far more mobile and quicker… [Without telephones] you just had to rely on people knowing what to do, particularly towards the end of the service to Lord Howe. If there was any doubt about an aircraft overnighting or having to be delayed for some reason or other, I’d have notified all the guest house proprietors and all the other men concerned: Department of Civil Aviation, Stanley Fenton [Island radio operator]; and Harry Woolnough, who operated the crash boat; and all the launch proprietors who serviced the flying boat once it arrived. They all had to be notified, and they were told exactly what to do and when to do it, and it all worked out very well…

Messages to the mainland: Well, they had to go by telegram or by radio telephone. DCA and the meteorological people both had a radio telephone link with Sydney, but they weren’t always successful. Often, because of radio conditions, we had to send the message to Sydney via Norfolk Island, which is quite a deviation if you think about it.

The joy with the difficult times was to sort them out, fix them up and get rid of the plane safely and happily. In mid-summer [I’d often start] at 1.00 am in the morning. Because of the 30-minute time lag [between Lord Howe and the mainland] it would be 1.30am Sydney time, followed by a three-and-a-half-hour flight over. That would be about 4.30am or 5.00 am Island time… first light. The planes would land and take-off and be back in Sydney by about 8.00 o’ clock in the morning.

On the mainland, there would have been a ready supply of telephones and easier communications with the headquarters of the Company.

The Last Flight on September 10th, 1974: [I felt] relieved, only because on the last flight surely there wouldn’t be a delay, or a problem, or an engine failure – not that it happened very often – but it was a sense of relief. I suppose it was the end of an era for me as well as the flying boat. They offered me the job of looking after Connellan Airways which was starting to operate into Lord Howe but, unfortunately, I was not able to do this… and so Barry Thompson took over and did a very good job.

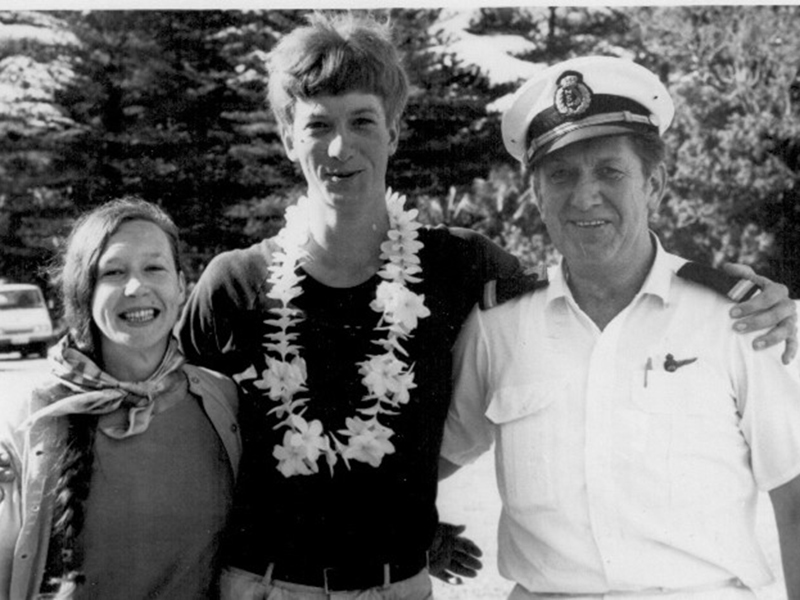

There were notably two people I would like to mention who were a marvellous help and assistance over the years. First off is the lady I met and married at Lord Howe Island, Jann Garton who, as my wife, helped tremendously in the entertaining of notable people on the Island. She could whip up a beef bourguignon at the drop of a hat and be the perfect hostess as required. …Such people as Gough Whitlam and his wife, Margaret, Al Grasby and his wife [Ellnor], just to name a few of the many people who visited the Island and we were able to, in our role as representatives of the Airline, make their stay a little more pleasant…

The other person I would like to mention… was my friend, Horton Ward, who was the Superintendent of the Island for many of the years that I was Manager of the flying boats. In a crisis, Horton always seemed to be there willing to help. Horton Ward was a marvelous Superintendent. He seemed to have the wellbeing of the Island at heart and, of course, the Airline. It was once said by a Sydney columnist that he had the wisdom of Solomon and the patience of Job, and this was a very true assessment of a very stable and solid person… All the other people, all the Islanders, sometime or other, also helped the airline….”

Addendum

In the above interview, David completely glossed over the logistical complexity of his job. It wasn’t a problem if flying boats were arriving, say, after 9.00 am, as people were generally up and about by then.

They could be easily informed of the arrival time via a sign outside the Department of Civil Aviation, the Island’s communication hub. However, what do you do when the DCA staff are home in bed, along with the rest of the Island, when a flying boat is departing from Rose Bay (or maybe cancelled due to weather) at 1.30am in the morning? Remember there were no phones, faxes or internet in those days, and flying boats simply couldn’t afford to wait around at Lord Howe if passengers were late – they could only operate safely an hour either side of high tide.

Fortunately, the Bureau of Meteorology maintained a 24-hour shift at the local weather station. They, at least, had a radio telephone with which the weathermen could call the mainland. Assuming the flying boat had departed, the information then had to be disseminated to the launch operators (who were responsible for disembarking passengers, baggage and freight) and to the Island lodge owners (who had to transport outbound guests to the jetty terminal and meet inbound ones).

Without modern communication, the only way to do this was person to person. David would mount his trusty Rabbit motor scooter, visit the Met Station at 1.30am (or whenever the early flight was departing Sydney), then do the rounds to every lodge and boat operator. He not only knew where they lived, he also knew in what room they slept! If they needed to know about a flight, he’d tap on the outside of their bedroom window and call out something like: “Flight arriving at 5.30am, please have your passengers and bags at the jetty by 5.00am”.

A list of lodges published in the Signal in 1961, names ten lodges, but this grew to at least a dozen by the time the service ended in 1974, so the round trip (at 10-15 minutes per lodge) could easily take David up to two hours in all weathers.

After this, he’d have to hurry to the jetty terminal to prepare for the flying boat arrival: passengers had to be checked in, their baggage carefully weighed, seats allocated, and a weight and balance sheet prepared for the aircraft. David routinely had to deal with 42 passengers per flight – 10 more than todays’ Dash 8 – 200 aircraft. Occasionally, on busy days, two flying boats would arrive together, so David would have to manage the baggage and check-in for 84 passengers.

Frank Chartres, a good friend of David’s, who visited Lord Howe regularly and who rented a small flat from him in the early 1970s, also helped towards the end of the flying boat service on these early morning rounds. Frank recalled: “He [David] had to go to the Met. Office in any sort of weather that occurred and at all sorts of hours, including 1 o’clock, 2 o’clock in the morning, to get Met. reports and find out what time the flying boat was leaving Sydney. Then he could go around to all the guesthouses and either tell them the flight had been cancelled or what time they expected the aircraft. He’d go off on his little motor scooter, and I’d go off on my little motor bike and I’d sometimes do the south end of the Island and he’d do the north calling into the different guesthouses and telling them, the proprietors, what the plans were for the arrival of the flying boat times…That was marvellous. First of all, it got me out of bed and into some of the most beautiful nights… it’s at night that the Island is really absolutely magnificent!!!…”. Magnificent for Frank, maybe, but certainly not for David, who had to ‘do the rounds’ hundreds of times in the dark – often in miserable weather – over 16 years as Ansett’s local flying boat manager!

Postscript

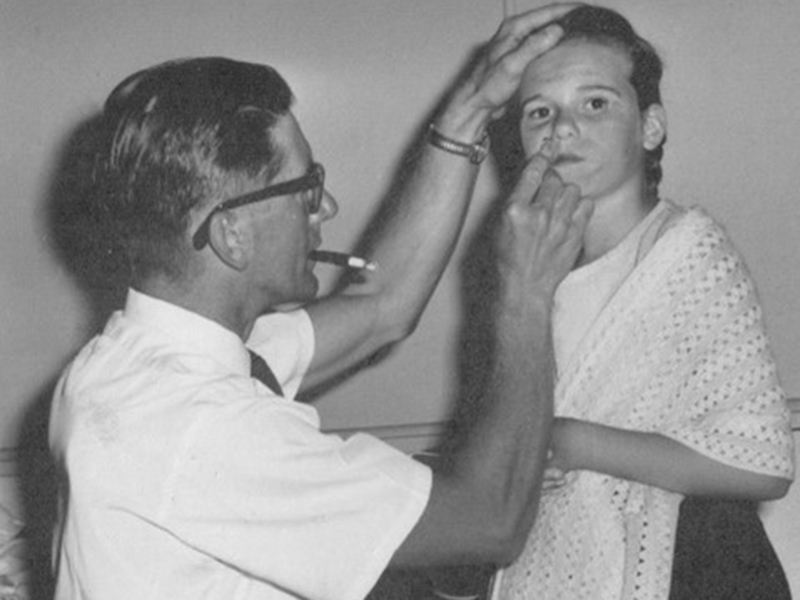

David was not only Ansett’s Lord Howe manager from 1958 to 1974, but also became part of the vibrant ‘60s Island entertainment scene, particularly at Tradewinds cabaret, and at community concerts, where the Tradewinds combo performed live with other artists. David also assisted at community entertainment events like school concerts.

SOME OF DAVID’S MORE SOCIAL ENGAGEMENTS ON LORD HOWE