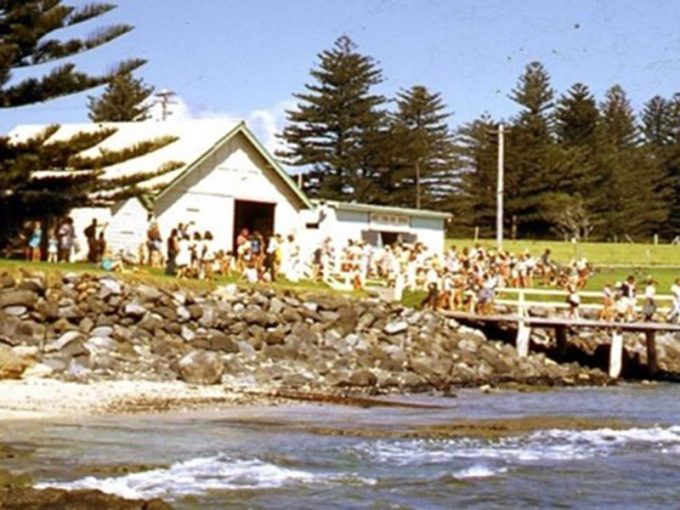

Growing up on Lord Howe during the halcyon days of the flying boats, the Lord Howe waterfront seemed like a sea of tranquillity: cheerful crowds congregated at the jetty to greet and farewell passengers; flower leis were romantically cast into the lagoon by departing passengers; Hawaiian music was piped in the vicinity of the jetty; and it all happened against the backdrop of Lord Howe’s opalescent lagoon and towering southern mountains… surely the picture-perfect setting? Although flight cancellations often occurred when the weather was inclement, on the good days it might easily have been a scene from the “Truman Show” – that quirky 1998 movie in which the chief character discovers his entire life has been lived inside the set of a benign reality TV show…what a thought!

It so happened, in 1997, I was helping the Museum Curator, Jim Dorman, with an exhibition to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the commencement of flying boat services to Lord Howe. One of the invited guests was Bryan Monkton whose airline, Trans Oceanic Airways, had initiated the very first flying boat service to the Island fifty years earlier. During World War II, Bryan had risen to the rank of Squadron Leader in the RAAF by flying an assortment of maritime aircraft including ex Qantas C Class flying boats, Dornier Do24s, Martin Mariners, and Catalinas.

Following the war, he launched a commercial airline utilizing converted wartime Sunderlands, piloted by men who had earned their wings during the war.

The commencement of TOAs service to Lord Howe, in August, 1947, was followed by Qantas in December of the same year. Consequently, Jim Dorman’s 50th anniversary exhibition featured both airlines.

However, when Bryan Monkton heard that Qantas had been included he was deeply offended. After all, hadn’t his airline been the first to start the Lord Howe service…why should Qantas share the stage? Eventually, however, he was persuaded that the Island Museum could not favour one operator over the other. Both airlines had commenced operating in 1947, so surely any 50th Anniversary display had to include both?

At the time, however, I was perplexed…wasn’t everything back in the flying boat days in the “happy holiday” department?

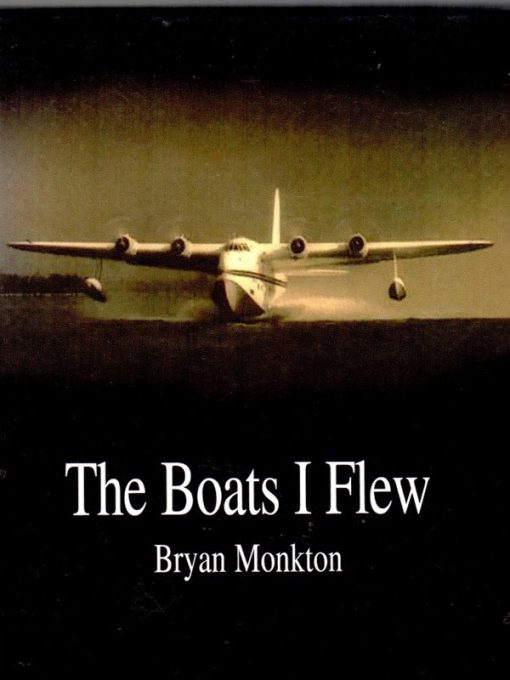

Some years later, a well-documented personal memoir by Bryan Monkton was published under the title of “The Boats I Flew” (Australian Aviation Museum, Sydney, 2005). This chronicled the constant frustration experienced by Trans Oceanic Airways as it endeavoured to compete with Qantas in the post war era. The many hurdles it faced were detailed in a chapter titled “The Adversaries – Tough, But Not Particularly Honest”.

After reading this chapter, I understood Bryan’s ire. In addition to the many obstacles placed deliberately in TOA’s path by government bureaucrats, accusations of sabotage were imputed against its Chief Pilot, Phil Mathieson, when a Qantas Catalina washed ashore near the Island jetty in June, 1949. Four months later, in August 1949, Bryan Monkton himself, was charged with sabotage when a Qantas Catalina exploded and sank on its mooring at Rose Bay. However, following a trial by jury, Bryan was acquitted.

So…the early flying boat days did produce some bright sparks – of the more incendiary kind!

In the next three episodes of Sparks from the Past, we’re going to look, firstly, at Bryan Monkton’s struggles to start the Island’s first flying boat service in the face of constant bureaucratic obfuscation; and secondly at the wild (or wiley?) accusations of sabotage imputed against TOA senior personnel. We’ll look at these events from both sides, quoting not only from Bryan Monkton’s “The Boats I Flew” (currently out of print) but also from “Wings to the World” by Hudson Fysh, Managing Director of Qantas from 1923 to 1966, and lastly from personal interviews given by TOA’s Chief Pilot, Phil Mathieson.

Lord Howe’s First Airline Service – Plenty of Turbulence Up There!

Before World War II, Lord Howe had enjoyed modest prosperity. The palm seed industry, in which all Islanders were shareholders, had continued throughout the Great Depression and there was a small but thriving tourist industry derived from passengers who arrived on the Burns Philp trading ships.

Up to 50 visitors could arrive per voyage, and they stayed either ten days or three weeks depending on whether Burns Philp scheduled a “short” or “long” trip. Small cruise ships had also started to include Lord Howe in their Pacific itineraries, bringing their shipboard passengers ashore for a day or two.

After World War II, however, Lord Howe was in the economic doldrums. The Burns Philp fleet had shrunk due to wartime losses and general attrition on their vessels due to age. Harry Woolnough, the local Maritime Officer with the Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) also commented ‘B.P., because of the demands of the seagoing unions, decided to get out of shipping where ships were manned by Australian crew and this left the opening, no doubt, for a flying boat service…” The feasibility of such a service had been demonstrated during the war: firstly, owing to regular flights between Lord Howe and Rathmines by RAAF Catalina flying boats from 1942; and, secondly, because the Lagoon at Lord Howe had been surveyed as an emergency stop-over point for flying boats which flew weekly between Sydney and Auckland. (One such aircraft, ‘Awarua’, did actually make an emergency stop in April, 1943, when one of its engines failed.)

As early as May, 1940, the Lord Howe Island Board demonstrated foresight in a Circular to Island residents when it stated: “…it is felt that the establishment of a flying boat service between Sydney and Lord Howe would…contribute immeasurably to make Lord Howe one of the leading, if not the premier tourist resort of Australia. Whilst the existing war situation may preclude the inauguration of such a scheme at the present time, the Board is hopeful that ultimately Lord Howe Island will have regular aerial communication with the mainland. To this end, it has approached the Premier of New South Wales and requested that…the question of aerial transport between Sydney and Lord Howe Island be taken up specifically with the Commonwealth Government.”

In the immediate post-war period, there was a false start when a company called Marinair made one commercial flight to the Island in July, 1946, utilising an ex wartime Catalina. Marinair, however, went into liquidation shortly after. The first successful service was another post-war start-up, Trans Oceanic Airways. Its Managing Director, Brian Monkton, had to his own amazement, almost serendipitously acquired a fleet of five ex war Sunderland flying boats after putting in a “token tender” towards the end of 1946.

What follows is a greatly foreshortened version of the events described his book “The Boats I Flew” (Some “editor’s notes” have also been added where I feel some point needs emphasis or clarification):

“…one morning the phone rang and a former Air Force colleague asked me to go with him to the RAAF Station at Rathmines to look at some Catalinas that were up for sale…my friend seemed to think a second opinion might be helpful in making a selection….Having made his selection, my colleague went off to stake his claim while I wandered along the shore of the lake to get a closer look at some aircraft that had been attracting my attention….

They were Sunderlands….this was no toy. It was a 28-ton, four engine aircraft, one of the largest in existence at the time…So I decided to put in a token tender… filled in the tender form and enclosed a cheque for the required 10% deposit of £600…The months went by… but one fateful day, just when I was about to complete the purchase of a small citrus orchard, a letter came from the Disposals people briefly informing me that my tender had been accepted and would I please pay the balance of the money as well as removing the aircraft and equipment from the RAAF property within 21 days!….

So here I was, at the age of 29, the owner of not one but five large aircraft. It was both a thrilling yet frightening situation and I went through alternate fits of elation and despair”. (Pp. 61-74)

Despite seemingly insurmountable hurdles, Bryan Monkton’s new airline, Trans Oceanic Airways, was duly incorporated and launched on 24th February, 1947. Brian Monkton, had always hoped that a Sydney-Lord Howe service would be a viable start-up but “when I applied to the Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) for an airline license for this route, I got a shock. The Department had surveyed the lagoon and decided it was too shallow for aircraft as large as the Sunderland, with its draft of six feet. Only flying boats, I was told, no larger than a Catalina, which drew under three feet, would be allowed to operate to the Island.”

However, circumstances gave Brian an unexpected opportunity: “Having delivered the propeller shaft [to Fiji] we took off on the return flight to Sydney…setting a course that would take us over the southern tip of New Caledonia, then over to Lord Howe Island…The island was long, narrow hilly and even mountainous at one end. …the large coral reef protected lagoon was ideal for flying boat operation.

Admittedly the lagoon was shallow and at low tide only had three or four feet of water over the bottom. This made it impossible for the Sunderland, whose keel ran six feet below the surface, to land at all times of the day and the DCA had ruled that only flying boats no larger than a Catalina would be permitted to land at the Island. I had argued that restricting our operations to the varying times of high tide we could provide a satisfactory service but the DCA was adamant that the service should be able to operate to a regular timetable no matter what the state of the tide…” [Editor’s note: This was bureaucratic “guff” because, even when the Government-owned Qantas Airways started its Catalina service to Lord Howe, it too varied the schedule to allow for arrival within two hours of a full tide…]

Brian continued: “Two local syndicates [in Sydney] that had each bought a Catalina were getting nowhere. They had no capital, no maintenance base and no one to organize their operation. In the meantime conditions on the Island were becoming serious. There had been no ship for months, food and other supplies were running low, the Islanders could not get their produce to the markets and there has been no money-producing visitors since before the war. We tried to convince the DCA [Department of Civil Aviation] that the Catalina was not the right aircraft. But our argument fell on deaf ears.

The most vocal and active person on the Island who recognized the value of the Sunderland over the Catalina was a man named Gerald Kirby. His family owned Pinetrees, one of the two guesthouses on the Island. Naturally, he wanted a reliable connection with the mainland that could bring visitors to the Island – and his guesthouse. He continually lobbied the government and made frequent visits to our office urging us to keep pressure on the DCA.

I was turning all these things over as we neared the Island. It was a cloudless day and, while still 60 miles away, the peaks of its two lofty mountains could be seen rising above the horizon.

As we came over the Island, its extraordinary beauty was obvious, even from 8,000 feet. There this gem lay in the setting of a dark green ocean, the thin white line of its reef stretched across the two ends of its crescent shape like a bow-string, enclosing a lagoon the colour of pale aquamarine.

The thought of flying regularly into such a lovely place filled me with a burning desire and suddenly, on an impulse, I decided to hell with the DCA, we would go down to have a close look and maybe even try to land.

We didn’t know the state of the tide so called the Island and were told it had been full only half an hour before. I felt sure there would still be sufficient depth if we got in and out quickly. I nodded to Taylor [the First Officer] who pulled back the throttles and started the landing checks. ‘You’d better tell Sydney we have a mechanical problem and are making an emergency landing at Lord Howe,’ I instructed our radio officer. ‘We’ll give them a new time of arrival later.’ I hated to lie to our friends in air traffic control but was determined to try to settle this matter.

Circling down, we made a low pass over the lagoon. It was a shock to see the white coral bottom as clearly as if there was no water at all and at first I thought there must be some mistake in the tidal information we had been given. We checked with the Island again. No, it was only just past high tide and there would be about 10 feet of water in the lagoon. Despite this assurance, it was an uncomfortable feeling to be alighting on water that appeared to be only a few inches deep and, as we were finishing our run towards the two towering mountains at the southern end, I waited in some trepidation to see what would happen when the aircraft came off the step and settled into the water. To my relief all appeared to be well and I turned back towards a boat putting out from the shore.

Stopping the engines, we let the aircraft turn up into the wind and, as it drifted back, the crew dropped the anchor where it and its chain could be seen lying on the coral as clearly as though looking through plate glass. Then a large open motorboat came across our bows and I recognised its driver as Kirby who greeted us with a broad grin and many thumbs-up gestures.

The caption reads: “Trans Oceanic Airways flying boat with ‘Albatross’ alongside, with Kirb at the wheel, about 1948”

‘I told you it would be all right,’ he shouted as he brought his boat alongside. ‘Now you should be able to convince those idiots in the DCA.’ Kirby was soon on board followed by a dozen tanned young men, wearing shorts and no shoes. They were all talking at once and bubbling with enthusiasm at what they seemed to see as the solution to their problems. After a while another boat came alongside containing an elderly gentleman and two women. The man called out. ‘These two ladies would like to be your first passengers to Sydney, please. What will the fare be?’ ’Charge them 10 quid each,’ said Kirby. ‘They can afford it.’ ‘No. we can’t do that.’ I replied. ‘On this occasion we’d be pleased to take them as our guests.’

While all this was going on time was passing. We had already stayed much longer than intended and it was clear the tide was falling rapidly. In some haste, we boarded our two passengers and persuaded the others to get back into their boat. Quickly closing the hatches, we hauled up the anchor and started the engines. As we taxied down-wind. Taylor and the flight engineer carried out the take-off checks. It was now almost half tide and I dared not go too far in case we ran into a shallow area where the aircraft could be stranded. Suddenly we felt the keel brush the bottom a few times and, in some alarm, I turned back into the wind, opened up the four throttles and got in the air.

I was rather pleased to have got away with this clandestine visit as it had enabled us to ‘show the flag’ to the Islanders and prove our argument, but the smile was taken off my face when, next day, I was summoned to the office of the Regional Director of Civil Aviation and found I was in trouble.

‘You really are a damn fool,’ said the regional director, a former senior Air Force officer who obviously thought he should still address me as a subordinate. ‘You send a signal to air traffic control saying you are making an emergency landing at Lord Howe with ‘technical trouble’ but when we checked we found no one on the Island saw your engineer working on the aircraft, and our inspectors at Rose Bay received no report on the nature of the problem. Obviously it was just a ruse to land there in defiance of our ruling on operations to the Island.’

I had no reply to this and sat awaiting sentence, all my hopes dashed to pieces. ‘I must also remind you,’ he went on sternly, ‘that you entered Australian territory at a place where there are no facilities for customs, health or immigration clearance. To cap it off you brought two domestic passengers into the country on an international flight which caused problems for the health and immigration officials at Rose Bay. Your passengers had to be vaccinated immediately or they would have been in quarantine for six months. So you, as Captain of the aircraft, might be in serious trouble with the relevant authorities which could result in a heavy fine or even a gaol sentence.’

This aircraft continued in regular service to Lord Howe until it was scrapped in 1951.

The regional director paused while I made the appropriate expressions of contrition, giving my assurance that nothing like it would occur again. I waited apprehensively while he was obviously deciding my fate. Eventually he said. ‘All right, I’ll accept your apology on this occasion. You’re lucky as I’ve also decided to take no further action on your escapade except to give you a strong warning and to advise you to act more responsibly in future.’

Then a faint smile spread over his face as he said. ‘Well, er — what about Lord Howe? We’re under pressure from the government to do something about that route. Do you think you could run a regular service there safely with your Sunderlands?’ ‘Yes, sir, I certainly do,’ I said, brightening up at this surprising question.

‘If we limited our operations to one hour each side of high tide and the shallow areas were marked off.’ ‘That would mean you couldn’t fly at regular times every day and schedules would be governed by the tide.’ ‘Yes, but the Sunderland would give the Island the sort of service it needs which, with respect, sir, the Catalina never could.’ ‘Hmm, I see. Well, I suggest you put in another application on those lines and I think it may be approved.’ And, to everyone’s surprise, it was. We now had, in addition to the Solomon Islands service, the route I had wanted originally. Everyone began to have more faith in the future, but then we didn’t know how rough the competition could get”. (Pp. 88-92)

Editor’s note: Bryan may have received a grilling from the NSW Director of DCA for his ‘clandestine visit’ to Lord Howe but, in the next two episodes, we see sparks really starting to fly when two Qantas Catalina’s are destroyed – one washed ashore at Lord Howe in a storm in June, 1949, and the other a few months later by alleged sabotage on its mooring at Rose Bay. These disasters were both imputed to malfeasance by senior TOA officers but, in both cases, the TOA was cleared of the accusations. Stay tuned for up-coming episodes of “Waterfront Wars”.